The earth where I was born was far down the face of a steep cliff and opened on a sloping shelf of turf, from the edge of which the undercliff fell sheer to the sea. The entrance we used most was slightly above the level of the springy sward and led by a small tunnel to a roomy chamber where daylight never penetrated. There on the bare dry ground the vixen laid us?my two sisters and me. If I was like the baby cubs I have since seen, I was born blind, my muzzle was blunt and rounded, and my coat as black as a crow, the only white about me being a few hairs in the tag of my tiny brush. Even at the time when I first remember what I was like my fur was still a very dark color and bore no resemblance to the russet hue of a full-grown fox. This was a few weeks after my eyes were opened, when, after awaking from our first sleep, we were in the habit of sunning ourselves just[Pg 10] inside the mouth of the earth. It was there, with my muzzle resting on the vixen's flank, that I got my earliest glimpse of the world. The turf was then almost hidden by pink flowers, over the heads of which I could see, between two of the pinnacles that bordered the ledge, the sea breaking on a reef where the cormorants used to gather at low water and stand with folded or outstretched wings until the rising tide drove them to the big white rock beyond. So few things moved within our field of vision that every creature we saw afforded us the keenest interest. Sometimes during days together nothing stirred but the stems of the thrift and the surf about the reef, for the sky was cloudless when the hot weather set in. Now and again a red-legged crow came and perched on one of the pinnacles, crying "Daw, daw!" until its mate joined it, and then, all too soon, they took wing and flew away; at times a hawk or a peregrine would glide by and break the monotony of our life. Our narrow green was dotted by five boulders, and one of these we could see from the earth. On this our most frequent visitor alighted. It was an old raven, who presently dropped to the[Pg 11] ground, walked up to the remains of any fowl or rabbit lying near the heap of sandy soil which my mother had scratched out when making the earth, and pecked, pecked, pecked, until only the bones were left. Then, uttering his curious "Cawpse, cawpse!" he would hop along the ground, flap his big black wings, and pass out of sight. I feel sure that he saw us watching him, for his eyes often turned our way. One afternoon, to our astonishment, a half-grown rabbit came lopping along, and stopped to nibble the turf at a spot barely a good spring from the vixen. She, usually very drowsy, half opened her eyes and turned her face towards the intruder, but she did not rise to her feet. We youngsters were beside ourselves with excitement, but were not allowed to scramble over her side to drive away this audacious trespasser on our private domain. This, I think, was owing to my mother's great anxiety on our account. I have never known a vixen so determined that her cubs should lie hidden by day; but then we were her first litter. She would constantly warn us against venturing out whilst the sun was up. So particular was she that we were not permitted to expose as much as our muzzles outside the[Pg 12] earth, though birds and rabbits moved about there freely. We could not understand the restriction, and I fear that we thought it unkind of her to confine us to a cramped, stuffy hole the summer day through, when we longed to be gambolling about the sward or basking in those warm corners under the boulders which retained some of their heat even after the sun went down. It is true that I tried hard to get my liberty. Time after time, when I thought she had dozed off, I endeavored to squeeze between her and the low roof. It was of no use, though I used the utmost stealth and trod as lightly as a feather. Never once did I catch her napping. On the few occasions when I was on the point of succeeding she seized me between her velvety lips and put me back in my place between my two little sisters. Thus, by the kindest of mothers, I was disciplined in the ways of the wild creatures, learning, by constant correction and example, that the world outside the earth is denied to us by day, and is ours to move and play and seek our prey in only by night. And how short those nights were! What a weary, weary time it was, awaiting their[Pg 13] approach! How impatiently we watched their slow advent! how we tingled with delight in every limb on seeing the shadow of the high boulder creep and creep across the turf until it reached the pinnacle that had a patch of golden lichen on it! Then, as the sun sank behind the headland, the nearer sea became sombre, the bright expanse beyond darkened, and at last the stars would begin to show in the sky. By this my mother had shaken off her drowsiness, the glow had come back into her green eyes, and, rising to her feet, she would leave the earth. If she detected no danger, she would call us to her. What a moment that was! the pent-up energy of hours of restraint breaking out in such rompings and runnings after our own brushes as I have never seen in any other young creatures. Wearying at last of these antics and of jumping over the back of the vixen, who watched us with loving eyes, we settled down to the game of lurk and pounce amongst the boulders. To our great delight, the vixen often joined in this before setting out in search of food. Her nimbleness and skill in dodging filled us with amazement. Like a flash she was on us; there was no avoiding her rushes, though she always avoided ours,[Pg 14] and her movements were as silent as the passing of a shadow when a swift cloud crosses the sun. I shall never forget those frolics in which she shared; they not only were useful training for the life before us, as I afterwards realized, but also induced in us a fondness for her so great that we could not bear to have her out of our sight when she left us to seek the food we needed. We would watch her as she followed the narrow track that wound up the cliff, till from the rocks near the top she looked down to assure herself of our safety before going inland. And that was not the last we saw of her. Times and times I have caught sight of her bright eyes glittering like twin stars on the summit of the ivy-covered scarp where the magpies built. A more affectionate mother cubs never had; but for the life of me I could not understand why she was so anxious about our safety: I had neither seen nor heard anything in our little world to alarm me. Whether she had or not I do not know, but she was haunted by the dread of something, as I could tell by the way she used to look about her and listen when watching our gambols, and by her starting at the slightest unusual sound. Her nervousness made me nervous,[Pg 15] and, thus infected by my mother's fears, I got to be afraid without in the least knowing what there was to be afraid of. These vague fears were on two occasions the cause of false alarms. Once, somewhere along the cliff a dry stick snapped. That was enough. My sisters and I fled in terror to our den, where we were joined a minute later by the anxious vixen who had just left us for a foraging expedition. There was no danger: it was merely a lumbering badger which crossed our playground later on; but I have learnt since that no wild thing can hear the snap of a twig without alarm. The badger was a strange-looking creature: his face was white, with black stripes from ear to muzzle; his gray hair all but swept the ground; and he walked not lightly on his toes as we do but heavily on the soles of his feet. At another time the whistling of harvest curlews frightened us almost out of our lives. These were both needless terrors; but soon I was brought face to face with evidence of a real enemy, the one, no doubt, of whom my mother lived in such dread. It was not many days after the coming of the whimbrels?for the moon, a mere sickle then, had not waxed to half its full[Pg 16] size?when two incidents occurred which proved to me, a raw, heedless cub, that there was serious ground for fear. Both happened in broad daylight, one close on the heels of the other. One drowsy noon we were watching from our usual place the old raven pecking at the hind-quarters of a rabbit, when with an awful thud a big stone struck the turf close to him, bounded off, and rolled towards the corner of our playground. In a twinkling, before it had stopped rolling, we had retreated to the very end of the earth and there lay trembling, and wondering, even in our consternation, whether the mischievous magpies, who had set up a sudden clamor, were not the cause of our discomfiture. When we stole out in the quiet and dusk, my mother walked straight to the stone and smelt it, and I, being curious, must needs follow her example. What an awesome smell it had! The scent was unlike anything I had sniffed before, and surely not the scent of any beast of the field! The vixen, who stood there watching me, noted the cold shiver it sent through my young limbs and seemed by her expressive face to say: "The creature that tainted that stone is the cause of all my fears," and, further, if I read aright the sad[Pg 17] look that rose to her eyes: "He will prove your scourge as he has proved mine." My story will tell whether it has been so. In our games that night I avoided the corner where the stone lay, and so did my sisters. I noticed, too, that the vixen was away in quest of food a shorter time than usual, and did not go out a second time as she had generally done since our appetites had grown. We had, therefore, to satisfy our hunger on the gosling she had brought. This we broke up ourselves with our sharp milk teeth, chattering and quarrelling as was our wont whilst the meagre feast lasted. The vixen contented herself with a few old bones. The other incident was graver, causing injury to my mother. It happened thus. She had gone out one night shortly after?for the moon was still not quite full?but, though absent till nearly dawn, she failed to procure any food. I remember our impatience at her long absence and our disappointment on seeing her issue from the furze without even a few mice in her mouth. However, there was no help for it. The sun was reddening the sky near the horizon, so, supperless and sullen, we curled ourselves up and fell asleep. On awakening, as we did before our[Pg 18] usual time, we began to cry pitifully for food, and at length, driven to desperation by our complaints, the vixen stole out at noon, not under cover of mist or fog but with the sun shining in the bluest of skies. Ravenous with hunger, we crowded the mouth of the earth, listening for the sound of her returning steps. Long, long we harkened without catching any whisper of her approach. At last we heard a muffled, double report, and after an interval the faint patter of her pads. In my anxiety to see what she had brought I put my head out and kept my eyes fixed on the run in the yellow furze through which she always came. Never shall I forget my horror at what I saw. Instead of her russet face with its black and white marking, her mask below the eyes was all blood and dreadful to behold. I am ashamed to say it, but her appearance terrified me, though I loved her as I loved my life. She staggered into the earth, and took no more notice of us than, if we had been strange cubs, which alarmed me more than her dazed look. The reason of her plight was a puzzle to me, and though the stone, with its horrid association, forced itself upon my notice as a possible cause, I dismissed the idea that it[Pg 19] could have done the injury, inasmuch as it was lying where it had rolled. No; in a vague way I attributed her state to the daylight, so great had my fear of it became. Ah me, how ignorant I was in those far-away days! We were free now to go and come as we listed, but, famished though we were, not one of us attempted to leave the earth except to get a drink of water, and we lay huddled together, looking out of the corners of our eyes at our poor mother, as miserable and forlorn a litter of foxes as could anywhere be found. In the depth of the night, however, the pangs of hunger compelling us, we left the vixen, who seemed to be asleep, and crept out. Being bigger than my sisters, I felt called upon to take the lead, and neither of them showed any inclination to dispute it with me. But where to take them, or how to get a supper, I had not an idea. I am not going to cast one word of blame on my mother for delaying to teach us to shift for ourselves. It was out of affection that she kept us so long to the nursery; and how could she possibly have foreseen the calamity that had so unexpectedly disabled her and thrown us on our own resources? And, lest a suspicion of neglect[Pg 20]towards us should attach to her memory, I must here say what I have not yet mentioned?that by the death of the dog-fox, my father, the burden of our upbringing from the day of our birth fell wholly on my little mother. What labor and sacrifice this must have meant! After we were weaned, how often have I seen her go without her share of the prey that we greedy cubs might suffer no sint! When has cliff or moor witnessed greater devotion, greater unselfishness? And now she lay in the earth so sorely wounded as to be indifferent to our helpless plight. I will not dwell on my feelings, but they made it difficult to focus my thoughts on the undertaking before me. For a minute or two I sat on my haunches near the big boulder, considering gravely where I should go, my sisters the while cruising restlessly up and down the turf with all the impatience of irresponsibility, awaiting development. This to-and-fro movement of theirs added to my bewilderment, and even the bats flitting about were a trifle disconcerting to a cub with three routes to choose from, each in its turn more inviting than the others. There was the patch leading to the upper cliff;[Pg 21] there was, I assumed, a way down the undercliff; and there was, I knew, a track between the two which the badger had worn. I have never been up the cliff, and after the vixen's recent experience dared not go, though it was night, and nothing stirred but the reeds about our drinking-place and the leaves of the gnarled tree where the magpies built. In the end I decided, if I could find a way, to go down the cliff. There was a sandy cove below that I had often longed to reach in my mother's absence, but my strength was unequal to the descent. I determined to try to go there now. So, leading the others past the little basin where we quenched our thirst, I brought them along the cliff to a place where the sheer precipice changed into a succession of ledges, down which we leaped until brought to a standstill above a wall of nearly perpendicular rock. It was impossible to reach the flat shelf below by leaping: we should have broken our bones; and there we stood staring over the brink at the smooth rock beneath us, and wondering how we could pass it. Again my sisters looked to me to take the lead, so, putting forth all the power of my untried claws, I began, brush first, to crawl down a[Pg 22] fissure that lay aslant the precipitous face of the great slab. This I followed, partly by feeling with my hind claws where foothold permitted a firm grip, partly by turning my face and seeing where the easiest line of descent lay. At last I succeeded in reaching the bottom without mishap. My sisters imitated me, coming down more easily than I had done, probably on account of their greater skill and lesser weight. A creek, too wide to jump, now separated us from the sand, but, taking to the water, we waded until we lost bottom, and then, for the first time in our lives, by swimming crossed deep water. More bedraggled creatures than we looked on landing it would be difficult to imagine; but we shook ourselves from muzzle to tag, making the spray fly from our wet coats, and set about searching for something to eat. Where the beach met the cliff was a cave that ran a long way in and had two lesser caves opening out of it. We explored these without finding in either of them anything except dry seaweed and pieces of cork, so we retraced our steps and made for the other side of the cove. There, just beyond the ribs of a wreck that projected from the sand, we came on a big jelly-fish. Though we should have[Pg 23] turned up our noses at such food in ordinary times, it was a windfall in our famished condition, and we swallowed the quivering mass with gusto, sand and all. Good food or bad, it filled our stomachs and stopped the gnawing pangs of hunger. We then clambered to the top of some rocks that stood out above the sand, and found there a small pool of water, temptingly clear. Being thirsty after our meal, we began to lap it. Ugh! it was nasty to the taste, but, what was worse, the mistake was a blow to my conceit, for I was humiliated by the reproachful glances my sisters shot at me. To avoid them I raised my eyes, and, as I did so, caught sight of the vixen on the cliff at the spot where we had taken to the ledges. Then it came home to me that I had done wrong to leave the earth without her, and, fearing she would be angry, I hid myself amongst the rocks, as did my sisters. The vixen, usually quick as lightning in her movements, came but very slowly down the cliff on the line we had taken, and as slowly crossed the sand to the cave. This she entered, and for a time was lost to view. My inclination nearly led me to quit my hiding-place and go after her; but again fear checked me,[Pg 24] and I remained where I was. On leaving the cave, she with difficulty followed our trail to the spot where we had eaten the jelly-fish, and, not seeing us, seemed to lose heart, for she sank to the ground and called us with a most piteous cry, which at once drew us to her side. I can see even now the delight on her poor face as we bounded towards her across the sand that separated us. After licking us with her swollen tongue, she led us up the cliff by a much easier path than the one we had followed in descending, and we soon reached the level of our earth. We proceeded towards it in single file by the narrowest of paths, passing our usual drinking-place, where for a reason I am going to explain, the supply was so scanty that we found barely enough water to quench our thirst. The vixen was curled up at the mouth of the den when we reached it, and we had to climb over her back to get to our sleeping-places. A short period free from troubles followed, during which my mother rapidly recovered. Nevertheless, the wounds on her face were barely healed when there befell one of the greatest calamities of my eventful life?a calamity that was near putting an end to us all. [Pg 25] Before attempting to describe it, I must mention the sufferings we endured in the days following our adventure down the cliff, through the gradual drying up of the water that supplied our drinking-place. Night after night, when we repaired to the basin that the falling water had hollowed in the rock, I had noticed that the stream, which came from some hidden source beneath a pile of boulders, got smaller and smaller, and, after the very hot weather set in, dwindled to a mere trickle. To such a thin thread did it shrink that from the mouth of the earth, which was not many yards away, we could no longer hear it splashing into the basin. Now and then, especially when some animal, generally the badger, had been there before us, we were driven to such an extremity as to be compelled to lick the dew off the turf to cool our tongues until the water had collected again. It was a terrible time. To this day we speak of the year of my birth as the Dry Year, and indeed I, who was a May fox, was nearly three moons old before I saw rain, which fell on the afternoon of the day when the curlews' whistling scared us. I remember, though not as vividly as the rainbow seen that day, the embrowned turf[Pg 26] of our playground being dotted with slugs which the downpour had enticed out of the sunless crevices of the rocks. The rain had ceased before nightfall, and the following day the sky, which had been black and lowering, became as cloudless as before, whilst the heat, previously intense, became well-nigh unbearable. Hour after hour we lay in the deep shade of the bracken fronds at the entrance, panting for breath and longing for the water we were not allowed to get before dusk. At the first sign of twilight, and even whilst the after-glow suffused the sky, we rushed to the drinking-place, our three masks completely filling the basin, which we soon lapped dry. Almost as refreshing as the water we swallowed was the cool spray?despite the rain it was no more?that fell on our heads from the lip of the rock above. For several days from dawn to dusk we thus endured the agony of parching thirst, till at last, when our tongues lolled out, and one of my sisters showed signs of utter exhaustion, the vixen so far yielded to our entreaties as to permit us to slink out, one by one, to drink. Unfortunately we could not reach the reeds about the water without exposing ourselves to the[Pg 29] eyes of the magpies overhead. On spying us they set up such a clamor that every bird and beast for a great distance along the cliffs must have known that a fox was moving, and rejoiced at our misfortune.

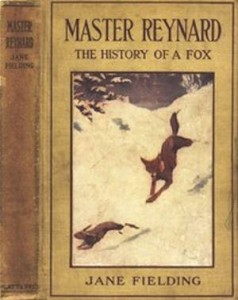

Master reynard (illustrated)

Sobre

Talvez você seja redirecionado para outro site