The 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, between Japan and China, brought an end to the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). That conflict pitted Japan against the imperial Manchu Qing dynasty of China. The war was sparked by growing Japanese interference in Korea, which had been a vassal or tributary state of China.

Since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan had undergone rapid modernization. Its institutions, military and navy had been remodelled along the lines of western powers, including France, Great Britain, the United States, and Prussia/Germany. China also made efforts to modernize its military in the 19th century, but modernization was less complete and less successful in China. The decaying Qing regime was weak and corrupt, the general population was relatively poorly educated in comparison to Japan, and there were powerful reactionary, conservative, anti-western factions who opposed reforms. The conservative faction was supported by the powerful Empress Dowager Cixi (Empress Dowager Tzu-his), who dominated China from the early 1860s until her death in 1908.

After being defeated by Great Britain in the First Opium War in the 1840s, China was forced to sign the first in a series of “unequal treaties”. In the decades that followed, other foreign powers extracted similar “unequal treaties” from China, including France, Russia, Germany, the United States, and Japan. These treaties were often obtained through the use or threat of military force.

The Chinese defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War and the Treaty of Shimonoseki that followed it was just one in a series of military defeats and unequal treaties at the hands of foreign powers. But the defeat of China by Japan was an especially significant humiliation for China, because the Chinese had traditionally viewed Japan as a subordinate or tributary state. Although Japan had not been under direct Chinese rule, it had historically paid homage to China and emulated Chinese culture and institutions. As a result the Japanese victory in the Sino-Japanese War discredited the imperial Qing regime, and stimulated reform and modernization initiatives, and Chinese nationalism.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, China made three territorial concessions to Japan. The Pescadores Islands (Penghu), Formosa (Taiwan), and the eastern part of the Liaodong Peninsula were handed over to Japan. China agreed to pay an indemnity, and opened four ports (Shashih, Chungking, Soochow, and Hangchow) to Japanese trade. Finally, China agreed to recognize the independence of Korea. It agreed that Korea would no longer pay tribute or perform ceremonial shows of subordination to China.

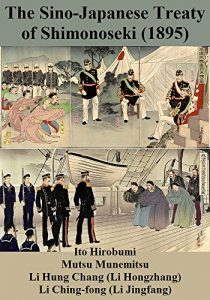

The treaty was signed by the Japanese Prime Minister Ito Hiroshima (1841-1909), and by Japanese diplomat Mutsu Munemitsu (1844-1897). On the Chinese side, the treaty was signed by Li Hung Chang (Li Hongzhang, 1823-1901), one of the most prominent statesmen and diplomats of the late Qing Empire, and by Li Ching-fong (Li Jingang, 1855?-1934), the nephew and adopted son of Li Hung Chang.

The Treaty of Shimonoseki set the stage for the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, as Russia and Japan competed for control of the newly-independent nation of Korea. After defeating Russia in that war, Japan incorporated Korea into its empire in 1910.

Since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan had undergone rapid modernization. Its institutions, military and navy had been remodelled along the lines of western powers, including France, Great Britain, the United States, and Prussia/Germany. China also made efforts to modernize its military in the 19th century, but modernization was less complete and less successful in China. The decaying Qing regime was weak and corrupt, the general population was relatively poorly educated in comparison to Japan, and there were powerful reactionary, conservative, anti-western factions who opposed reforms. The conservative faction was supported by the powerful Empress Dowager Cixi (Empress Dowager Tzu-his), who dominated China from the early 1860s until her death in 1908.

After being defeated by Great Britain in the First Opium War in the 1840s, China was forced to sign the first in a series of “unequal treaties”. In the decades that followed, other foreign powers extracted similar “unequal treaties” from China, including France, Russia, Germany, the United States, and Japan. These treaties were often obtained through the use or threat of military force.

The Chinese defeat in the First Sino-Japanese War and the Treaty of Shimonoseki that followed it was just one in a series of military defeats and unequal treaties at the hands of foreign powers. But the defeat of China by Japan was an especially significant humiliation for China, because the Chinese had traditionally viewed Japan as a subordinate or tributary state. Although Japan had not been under direct Chinese rule, it had historically paid homage to China and emulated Chinese culture and institutions. As a result the Japanese victory in the Sino-Japanese War discredited the imperial Qing regime, and stimulated reform and modernization initiatives, and Chinese nationalism.

Under the terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki, China made three territorial concessions to Japan. The Pescadores Islands (Penghu), Formosa (Taiwan), and the eastern part of the Liaodong Peninsula were handed over to Japan. China agreed to pay an indemnity, and opened four ports (Shashih, Chungking, Soochow, and Hangchow) to Japanese trade. Finally, China agreed to recognize the independence of Korea. It agreed that Korea would no longer pay tribute or perform ceremonial shows of subordination to China.

The treaty was signed by the Japanese Prime Minister Ito Hiroshima (1841-1909), and by Japanese diplomat Mutsu Munemitsu (1844-1897). On the Chinese side, the treaty was signed by Li Hung Chang (Li Hongzhang, 1823-1901), one of the most prominent statesmen and diplomats of the late Qing Empire, and by Li Ching-fong (Li Jingang, 1855?-1934), the nephew and adopted son of Li Hung Chang.

The Treaty of Shimonoseki set the stage for the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, as Russia and Japan competed for control of the newly-independent nation of Korea. After defeating Russia in that war, Japan incorporated Korea into its empire in 1910.